The feather of truth

My hands shook as I carefully removed the last of the stone blocks sealing the tomb of Ma’athotep—truth is satisfied—from its place. Everyone knew this was the right of the dig director alone—a custom established in the days of Howard Carter—and stood back. As the dust of three thousand years cleared, Mohammed shone a powerful torch into the darkness. Behind me, Clio screamed. René, our epigrapher, who hadn’t appeared for the tomb opening this morning, was naked and supine in the centre of the broad entrance hall, mouth open, eyes blank, an ugly wound on his bald pate and a bloody, gaping hole in the centre of his chest where his heart should have been. Hayden retched behind me.

‘Who could have done that to him? said Clio through sobs. He was a priest, for God’s sake!’

Hayden whispered through Clio’s hair as he turned her face from the grisly scene, ‘He never hurt anyone. He lived in his own world of hieroglyphs.’

I needed to take control. Action would slow my racing heart. ‘We can’t touch him, or anything else in here. We have to leave him exactly as he is for the police. I have to seal it up again.’

‘We can’t leave him like that,’ Clio said.

‘Why do we need the police?’ said Mohammed.

‘We’re in the middle of nowhere. It’ll be days before they get here,’ Hayden added.

‘We have to tell them,’ I said. ‘How do you explain how he got into a sealed tomb, without leaving a trace and then did that to himself? I broke the seal myself. You all saw me. He was murdered.’

‘But how?’ said Clio.

‘I know he was our friend, and we don’t want to leave him like this,’ I said, ‘but this is beyond any of us. Everybody out. We’ll talk about this later, when we’ve calmed down.’

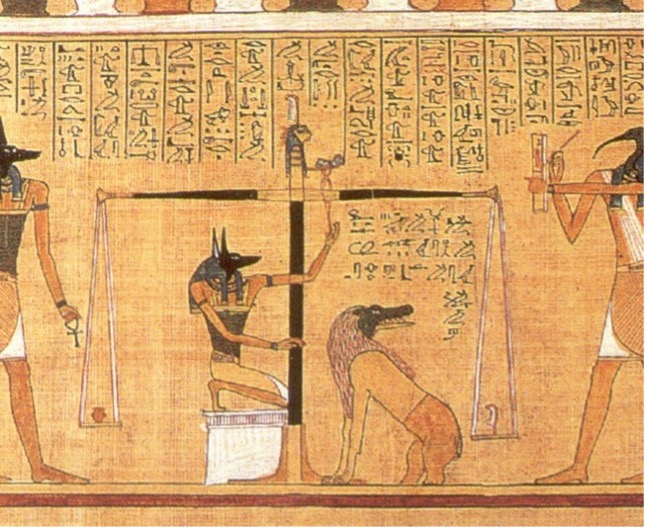

As I worked to reseal the tomb, my gaze was caught by a small, black scarab beetle crawling over the face of the ancient goddess Ma’at, the goddess of truth, justice and order. Her frontal eye stared down from her profile on the tomb wall as she weighed the heart of Ma’athotep against the feather of truth in the balance to rule on his fitness for admission into the afterlife. Facing her, the court recorder, the jackal-headed Anubis, god of writing, knowledge and wisdom, stood ready with reed brush in hand to record the result on his papyrus scroll. Behind Ma’at, the executioner, the demon Ammit, with the head of a crocodile, torso of a lion and hind quarters of a hippopotamus—the three most deadly animals in Egypt—waited to devour the heart, the seat of the soul, of any found not to have upheld truth or allowed isfet—evil or chaos—to enter the world. Lack of a heart would condemn the deceased to death in the afterlife, leaving their ba, or spirit, with an incomplete, unusable akh, or body, forever.

***

Clio stood motionless as a statue, facing out into the shimmering haze of the desert on the edge of camp. Our affair had been brief, but the physical attraction of her youth and vitality remained. ‘Boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away,’ I quoted from Shelley as I lit a cigarette.

‘It’s like a blank canvas, waiting for history to be written on,’ she replied.

‘Only by the winners,’ I said.

She turned to me. ‘Every time I close my eyes, I see that horrible scene. I can’t erase the memory. I’m a photographer. I work in pictures. They record everything faithfully and always tell the truth. But I can’t see what the truth is here.’

‘Pictures may tell a thousand words,’ I said, ‘but they don’t speak for themselves. We have to speak for them. It’s we who interpret the pictures. We have to try to understand what they’re telling us. Think. What is the picture telling you?’

‘I don’t know Jaques, I don’t know. I know the tomb was sealed. It had never been opened. The nine bows necropolis seal was intact. I thought, this is it! An unrobbed tomb; a famous discovery. We’ll certainly be famous now, but not for that. I can see the headlines: “Murder Victim in a Sealed Tomb”, “The Curse Strikes Again”.’

‘That’s rubbish. You know as well as I . . .’

‘Is it? How else . . . ?’

‘There has to be a logical explanation. There has to be. We just have to work it out rationally.’

‘Typical male. Rationality and logic; the answers to everything.’

‘There you go again. Do you always have to bring the sexes into it? You see everything through the same lens, and it only shows you what you want to see. What are you saying? Are you seriously asking me to believe René was somehow spirited into the tomb without opening it, and that some afreet, or demon mutilated him like that?’

‘No! Oh, I don’t know. All I’m saying is that I can’t think of a rational explanation.’

‘Well, the police aren’t going to swallow spirits and demons.’

‘There you go again. That’s sexist and offensive. You men are all the same; you assume superiority and put down anyone who disagrees with your logic. God forbid a mere woman should disagree with you.’

I was warming up: not just from the blazing sun. I opened my mouth for a pithy remark on feminist bias, but it shrivelled in the heat of her glare. I changed tack. ‘Were you like this with René? The church can be patronising and patriarchal. Did you quarrel with him like this? Or did he make a pass at you? Did you snap in the heat of the moment?’

I reproached myself as she stormed off, the accusation left hanging in the heat haze. Had I gone too far? Could this nonsense about spirits and demons really be a distraction? Her ending it between us still stung. Hayden wasn’t much younger than me. Was it clouding my judgement? Could I really find a motive there?

A faint screech on the wind made me look up to see a falcon wheeling high overhead. The god Horus: avenger of evil. I ground out my cigarette and turned back to camp.

***

Mohammed was readying our hired felucca to make the trip across to the east bank of the river. The nearest police taftish was almost 10 hours’ drive north from there. As I approached to make sure he knew what to say, yet another tourist boat floated south on the sluggish, brown mirror of the Nile, like the crocodiles and hippos they had driven from the river. It never ceased to amaze and annoy me how we could be so remote from civilisation, but not from one of its most insidious diseases—tourists eager to capture the soul of Egypt with their telephoto lenses, like the monster Ammit eating the heart of the deceased.

Mohammed hawked and spat. ‘Hawaga!’ A derogatory term he reserved for foreigners, especially westerners. He’d been university educated in Cairo and aired his nationalist, anti-colonialist beliefs at every opportunity. They extended past politics and history to what we were doing here. We’d had the argument often.

‘Who are you French and English to come to our country with your Indiana Jones hats, dig up our dead and write our history as if it’s yours? You’re like jackals at a carcass!’

‘But it’s not your past, you’re a Moslem.’

‘Who can say who owns the past? Can anyone own the past?’

‘Whoever has the scientific skills and knowledge should tell the story.’

‘You don’t seem to realise, that’s more western colonialism. You appropriate the story of the past and take away our right to tell it ourselves. You seem to think you’re doing us a favour, and we poor orientals should thank you for civilising us. I trained as an archaeologist and site inspector to tell our own story. René showed me the article he was writing on the scenes and texts of these tombs. It was a brilliant scholarly analysis, but not a word about our traditional beliefs. Still, he won’t be publishing it now.’

I needed to be clear on what Mohammed was going to tell the Police. ‘Just tell them what’s happened; don’t let them draw you into speculating about who you think might have killed René, or how. We have to leave that to them; we need to let them make their own conclusions, without anyone muddying the water.’

He stood and looked me in the eye. ‘I have my own ideas on what happened and who is to blame.’

I knew very well what those thoughts were. ‘You have to keep an open mind. You can’t let your prejudice blind you to the truth.’

‘You’re right Jaques, as always. I must keep an open mind. After all, there are several westerners here who could have done it.’

‘Is that what you really think? Does your prejudice go that far? You’ve conveniently left one person out. It’s clear you hate us. Are you going to turn the police against us? Do you have something to hide yourself?’

Mohammed gave me a blank look, spat again, and shoved the felucca off.

‘Just tell them to get here as soon as they can,’ I shouted after him.

I stood deep in thought, as the southerly breeze filled the lateen sail and the felucca picked up speed northwards across the current. ‘Did he really think one of us had done that to René? Would he spout his conspiracy theories to the police and bias them against us? Could he be concealing a deeper truth? Could his rantings against western archaeologists become more than just rantings? Was that enough motive?

***

Across the fire Hayden, our graduate student from Oxford, sat frowning, a nearly empty bottle of whisky beside him. There’s something about staring into the flames of a campfire at night, surrounded by nothing but brooding darkness that encourages deep thought. Things surface and are aired that would never see the light of day.

‘Penny for them?’ I said.

‘They’re not worth it.’ He replied, staring into the flames. After a long silence, he looked up and said, ‘You realise of course it has to be one of us. Who do you think did it?’

I thought for a long time, but there was no good answer to that question.

‘Come on! You must have thought about it. I’ve thought of nothing else for the last two days; it’s driving me mad.’

‘Yes, I’ve thought about it. I’ve spoken to Clio and Mohammed. They both denied it, but how do I know they’re telling the truth?’

‘Well, I know I didn’t do it—did you?’

‘No! Of course not. Be careful our familiarity out here doesn’t lead you to overstep the line between Professor and graduate student. I’m still your supervisor, and I don’t take kindly to . . .’

‘Then one of us is lying. That’s the problem we, and the police, have. We’ll all tell them the same facts, but place our own interpretation on them, from our own perspective, for our own purposes. It’s a helluva way to prove my argument, especially for poor old René, but don’t you see now that I’m right. Truth is relative to the observer. Each of us will tell the truth as they see it. There’s no such thing as an absolute truth. There certainly isn’t here. No-one’s going to put their hand up and say, “It was me. I did it. I killed him and here’s how and why I did it,” . . . I still can’t fathom either of those things.’

‘Yes, yes. All that may be so. But where does it leave us? I still contend that there has to be an absolute truth, even if we can’t get at it, it has to be there. Without it, where are we? I’ll tell you. Forever lost on a sea of fiction masquerading as “interpretation”. If you invite in relativism, you also invite in misrepresentation, deliberate manipulation and outright lies, with no way of telling any of them apart. We have to be able to say what’s true and what’s not, or we end up totally lost, with no compass. There have to be some accepted facts. We can’t deny what our eyes and brains are telling us . . . what actually happened.’

‘Do you think I’m lying then? I tell you; I didn’t do it!’

‘How do I know that’s the truth? Everyone’s denied it. According to your argument, I have no way of knowing the truth.’ Something occurred to me, and I thought, merde, in for a penny . . . ‘But is that what you want? Are you trying to hide the truth in this relativist claptrap of yours?

‘Don’t be absurd! What possible motive could I have for killing poor René, and how could I possibly have done it?’

‘It occurs to me that if you deny absolute truth, you deny the existence of God. Did you have that argument with René? I know he wouldn’t take that lying down. I’ve noticed our stock of whisky has dried up lately too. You’re the only two drinkers. Did you and he drink too much and argue one night? Did the argument get out of control?’

‘Go to hell! So what if we did like a drink and an argument. It doesn’t mean I killed him. You can’t prove I did!’ He threw the rest of his whisky on the fire. It flared up in my face, temporarily blinding me. When my vision returned, I was alone. Hayden and I had had our disagreements before, but that was just the young buck butting against the old bull. I hadn’t seen this kind of raw, physical anger from him before. A thought flickered and flared in my mind. Could he have done it? Was that enough motive?

***

I sat drinking shai and smoking a sheesha with Detective Inspector Girgis at al-Fashawi’s Coffee House in the Khan al-Khalii bazaar, Cairo. The thin, flat drone of the muezzin in the nearby al-Hussein Mosque calling the faithful to prayer reminded me of Father René.

‘So, as I see it,’ I finished, ‘they all have a potential motive.’

‘Even you professor.’

‘Me?’

‘Yes. I’ve just finished reading an article published in your name on the epigraphy in the tomb of Ma’athotep. It got outstanding reviews. It occurs to me that Father René’s name should have been on it . . .’

‘Which of us do you think did it, then?’

‘I know one of the four of you did. There’s no-one else. You were completely isolated. I’ve had four different answers from each of you. Four different perspectives on the truth. There’re too many different versions and interpretations of the truth, and too few actual facts in this case. One of you is lying. I know there is a truth, but it’s so deeply buried in lies and misdirection now, I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to make a provable case.’

I blew a ring of apple-scented smoke from my sheesha. ‘If not who, then, at least how?’

‘Now there I can tell you something. Our forensic team found clear evidence—scratch marks on some of the stone blocks of the door and on the floor of the tomb—that showed they had been removed and replaced more than once. Just enough to slide a body in,’ he said. ‘No-one else noticed them, but at least one person should have.’ As he drained his shai, his eyes locked onto mine. ‘I can’t allow what happened to be forgotten or buried in lies and half-truths. I’ll not allow the truth, the only thing René has left, to be taken from him. I owe him that.’ He got up and left. He was aptly named after the dragon-slaying St George, I thought. He knew, and he wasn’t going to let it go.

As I sat alone, I felt the eye of goddess Ma’at on me. Her scales and the feather of truth were waiting. Anubis’ reed brush hovered over his scroll and Ammit’s jaws dripped, but I had René’s heart. It couldn’t testify against me.